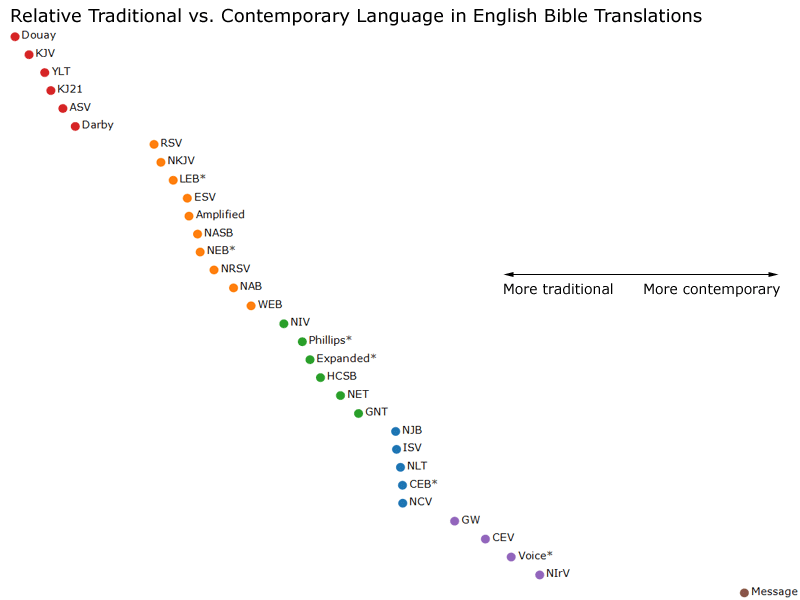

Using data from Google’s new ngram corpus, here’s how English Bible translations compare in their use of traditional vs. contemporary vocabulary:

* Partial Bible (New Testament except for The Voice, which only has the Gospel of John). The colors represent somewhat arbitrary groups.

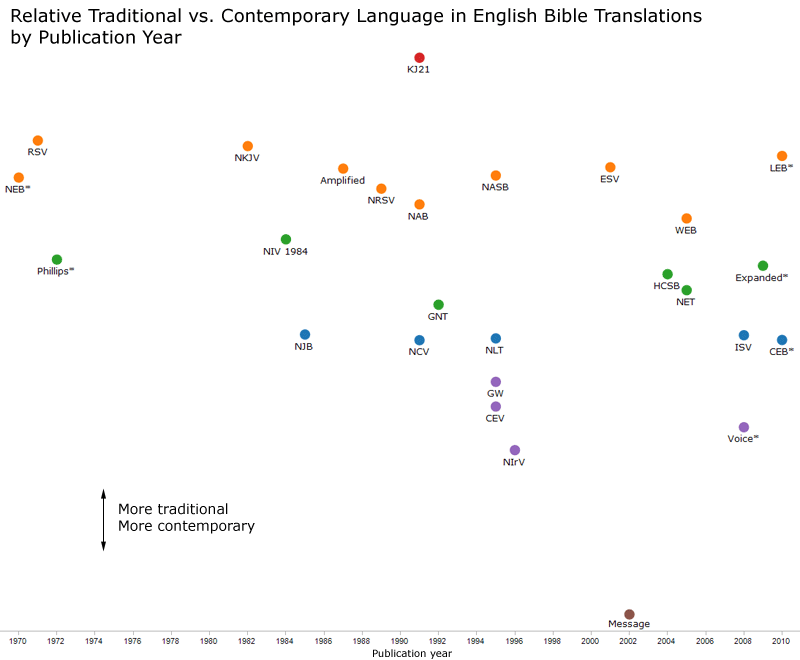

Here’s similar data with the most recent publication year (since 1970) as the x-axis:

Discussion

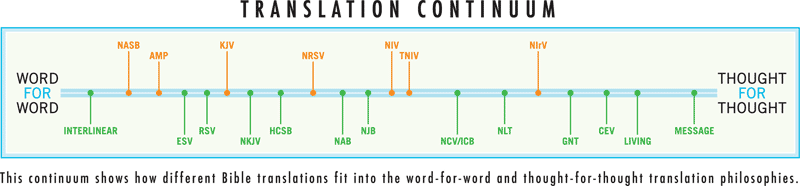

The result accords well with my expectations of translations. It generally follows the “word for word/thought for thought” continuum often used to categorize translations, suggesting that word-for-word, functionally equivalent translations tend toward traditional language, while thought-for-thought, dynamic-equivalent translations sometimes find replacements for traditional words. For reference, here’s how Bible publisher Zondervan categorizes translations along that continuum:

I’m not sure what to make of the curious NLT grouping in the first chart above: the five translations are more similar than any others. In particular, I’d expect the new Common English Bible to be more contemporary–perhaps it will become so once the Old Testament is available and it’s more comparable to other translations.

In the chart with publication years, notice how no one tries to occupy the same space as the NIV for twenty years until the HCSB comes along.

The World English Bible appears where it does largely because it uses “Yahweh” instead of “LORD.” If you ignore that word, the WEB shows up between the Amplified and the NASB. (The word Yahweh has become more popular recently.) Similarly, the New Jerusalem Bible would appear between the HCSB and the NET for the same reason.

The more contemporary versions often use contractions (e.g., you’ll), which pulls their score considerably toward the contemporary side.

Religious words (“God,” “Jesus”) pull translations to the traditional side, since a greater percentage of books in the past dealt with religious subjects. A religious text such as the Bible therefore naturally tends toward older language.

If you’re looking for translations largely free from copyright restrictions, most of the KJV-grouped translations are public domain. The Lexham English Bible and the World English Bible are available in the ESV/NASB group. The NET Bible is available in the NIV group. Interestingly, all the more contemporary-style translations are under standard copyright; I don’t know of a project to produce an open thought-for-thought translation–maybe because there’s more room for disagreement in such a project?

Not included in the above chart is the LOLCat Bible, a non-academic attempt to translate the Bible into LOLspeak. If charted, it appears well to the contemporary side of The Message:

![]()

Methodology

I downloaded the English 1-gram corpus from Google, normalized the words (stripping combining characters and making them case insensitive), and inserted the five million or so unique words into a database table. I combined individual years into decades to lower the row count. Next, I ran a percentage-wise comparison (similar to what Google’s ngram viewer does) for each word to determine when they were most popular.

Then, I created word counts for a variety of translations, dropped stopwords, and multiplied the counts by the above ngram percentages to arrive at a median year for each translation.

The year scale (x-axis on the first chart, y-axis on the second) runs from 1838 to 1878, largely, as mentioned before, because Bibles use religious language. Even the LOLCat Bible dates to 1921 because it uses words (e.g., “ceiling cat”) that don’t particularly tie it to the present.

Caveats

The data doesn’t present a complete picture of a translation’s suitability for a particular audience or overall readability. For example, it doesn’t take into account word order (“fear not” vs. “do not fear”). (I wanted to use Google’s two- or three-gram data to see what differences they make, but as of this writing, Google hasn’t finished uploading them.)

I work for Zondervan, which publishes the NIV family of Bibles, but the work here is my own and I don’t speak for them.