The images that come to mind when you think of heaven aren’t the same ones you would’ve conjured had you lived a hundred, five hundred, a thousand, or two thousand years ago. The word heaven accretes and shifts meaning over time–the cosmology of the Israelites who first heard the creation story in Genesis, for example, uses the metaphor of a “firmament” to explain the structure of the heavens, while your idea of the physical heavens probably involves outer space and Pluto.

Or take angels. Before the Renaissance, you wouldn’t have pictured a cherub as a chubby baby, yet today the first image that comes to mind when you think of angels might very well be this:

From Raphael’s Sistine Madonna, 1512

Linguists can pinpoint precisely when English speakers started to use cherub to refer to a child in this way: 1705. (The OED entry for cherub elaborates that this image developed further during the 1800s. Thank you, Victorians.)

Researchers from the University of Glasgow have created a website that explores how metaphors from different semantic domains (“angels” and “children,” for example) bleed into each other over time: Mapping Metaphor.

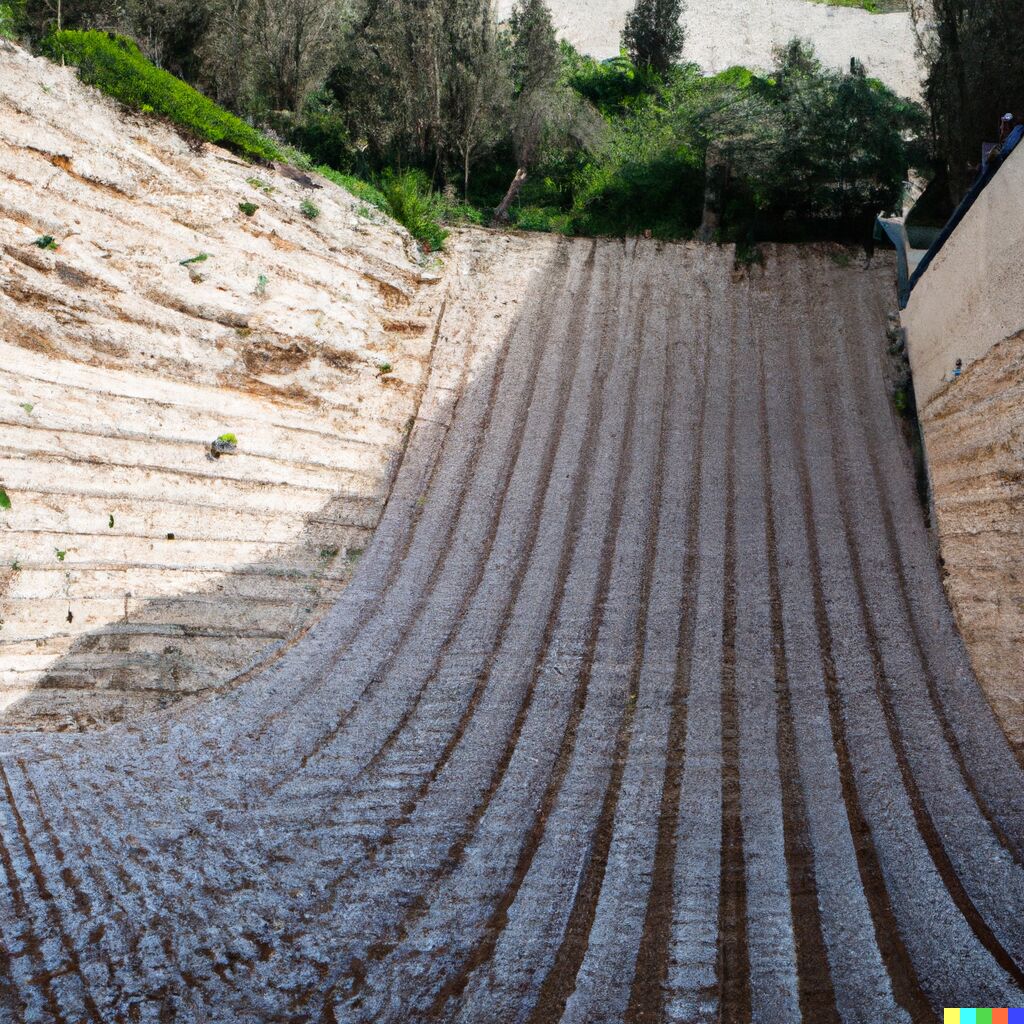

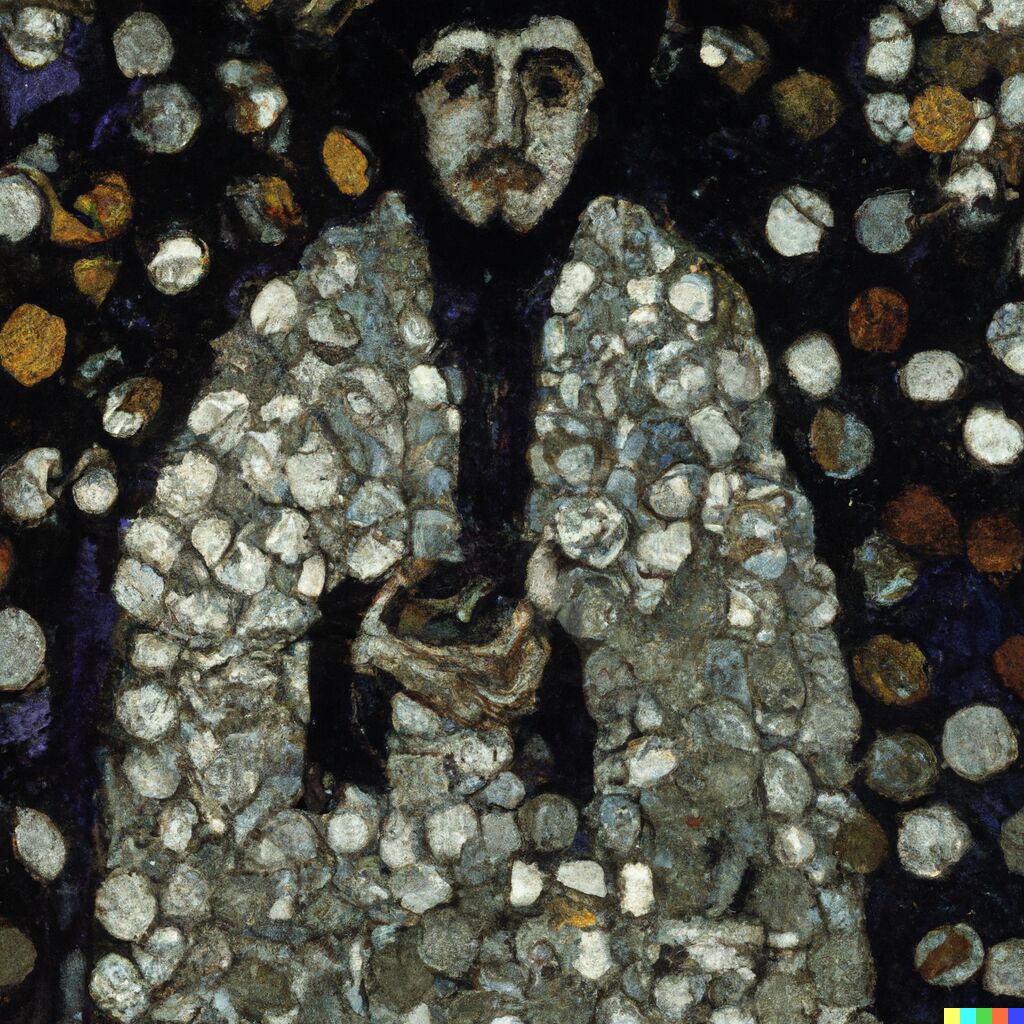

While the website lets you visualize the data in a number of ways, I thought it would be interesting to combine a couple of their visualizations to clarify (for myself) the historical cross-pollination of some Bible-related metaphors in English.

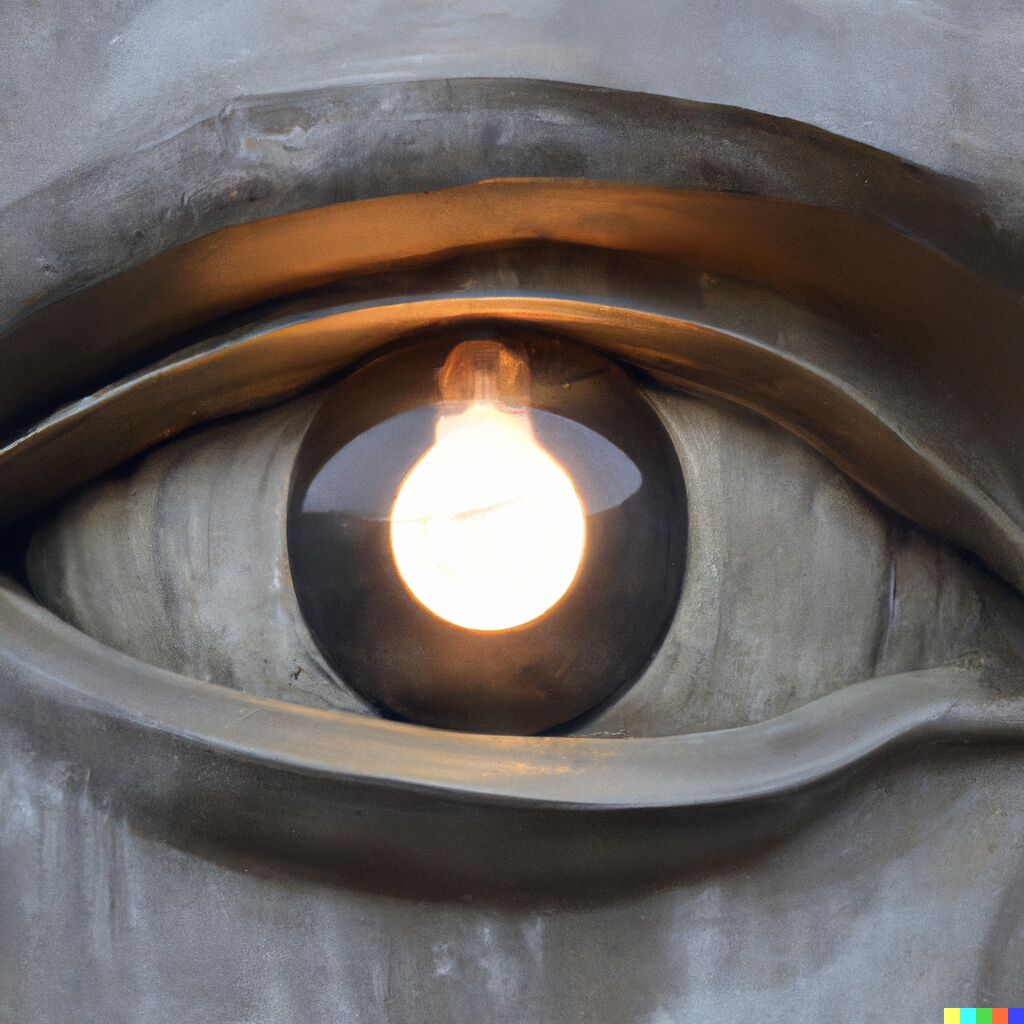

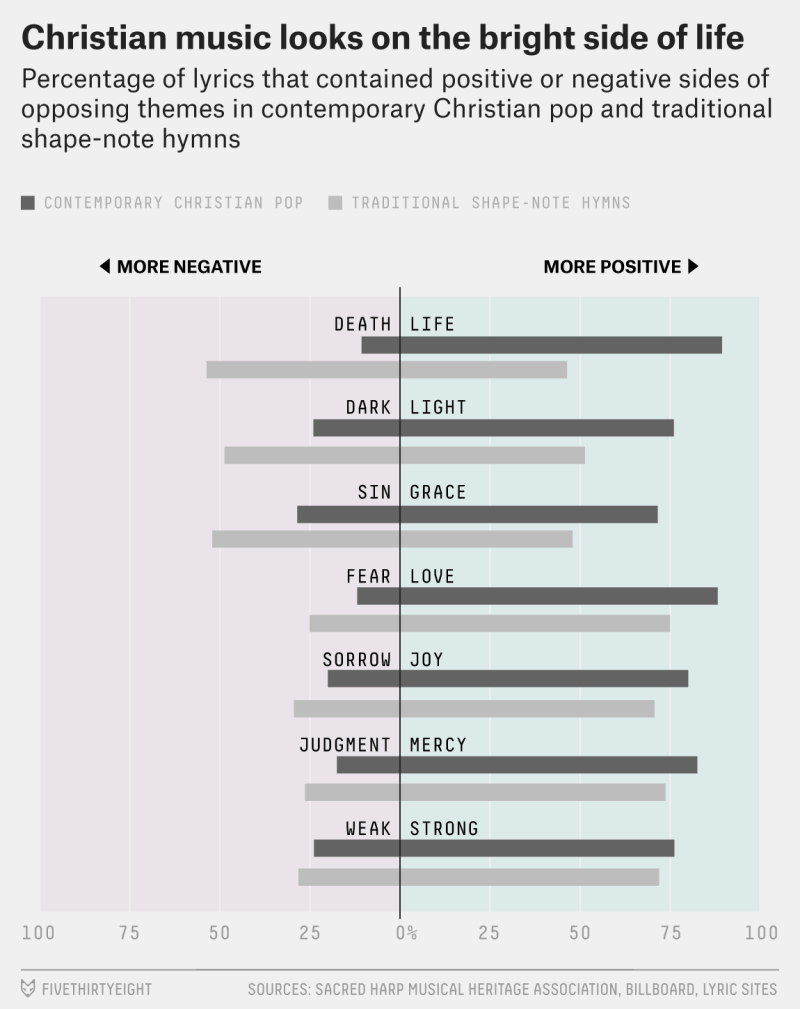

The first chart shows how metaphors have shifted over time for heaven and hell. The arrows indicate the direction of the metaphor. For example, an arrow points from height to heaven because linguistically we apply the real-world idea of height to the location of heaven: the metaphor points from the concrete to the abstract. Conversely, when the arrow goes the other direction, as from heaven to good, the metaphor points from the abstract to the concrete. When we say, “This tastes heavenly,” for example, we’re applying some qualities of heaven to whatever we’re eating.

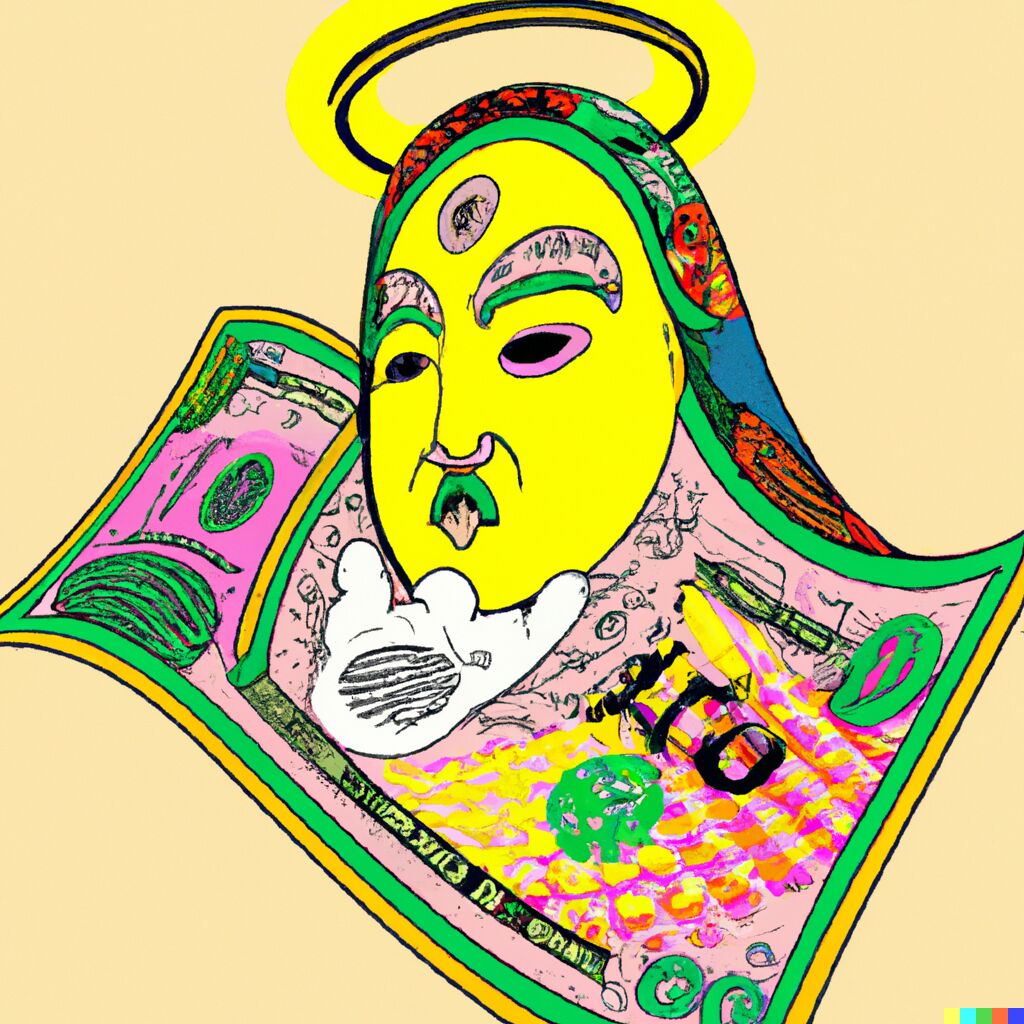

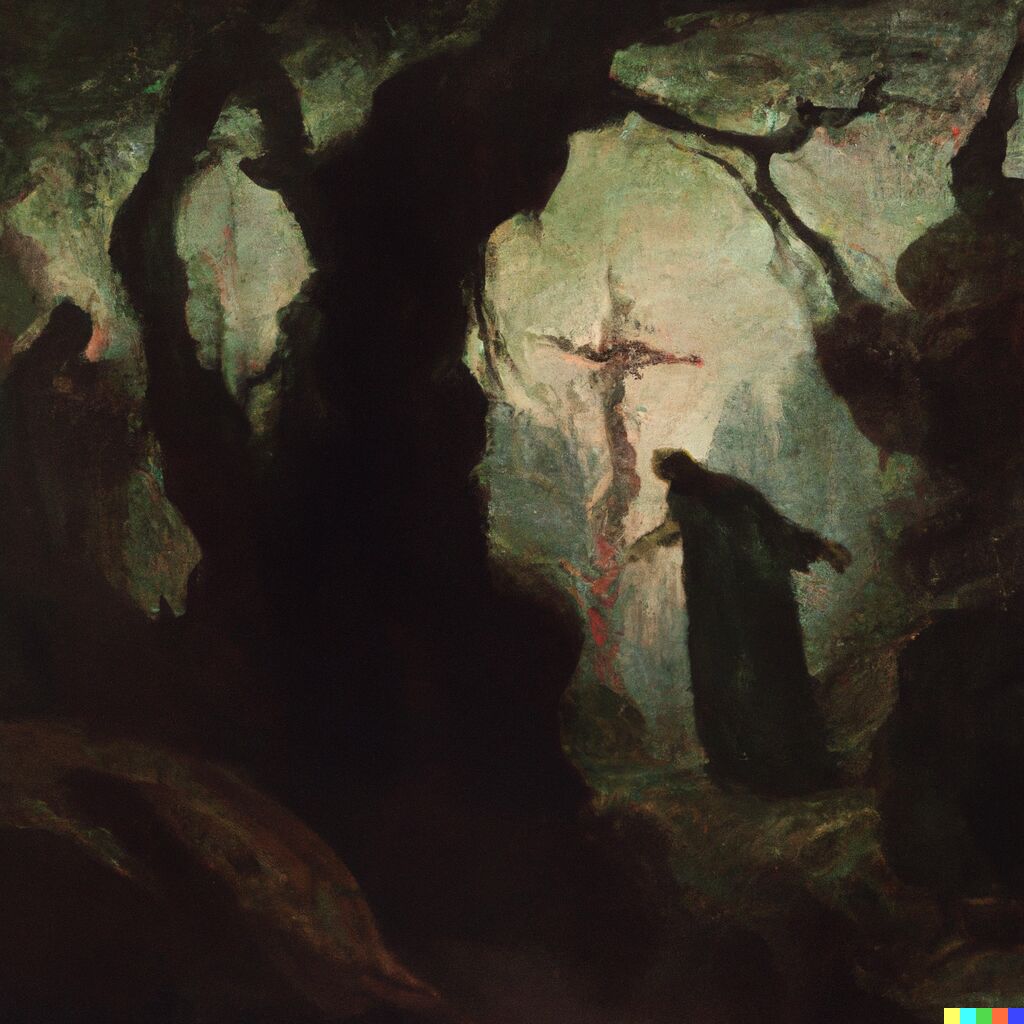

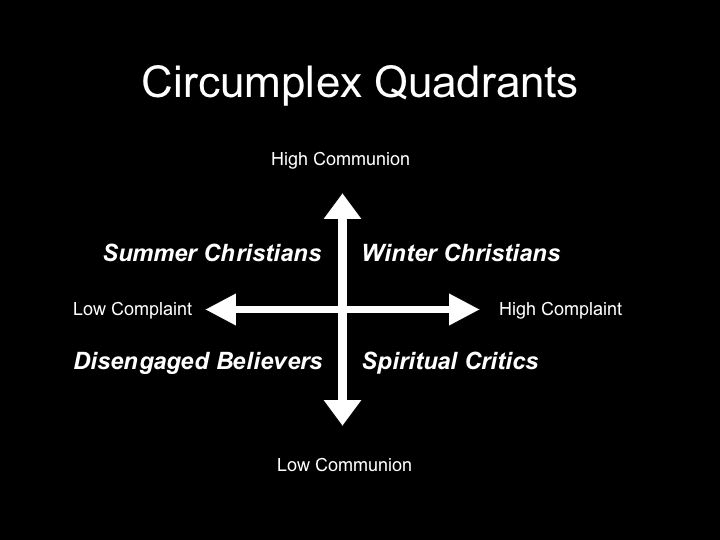

The second chart explores the application of metaphors relating to angels and the devil. The Mapping Metaphor blog discusses this metaphorical angel/devil dichotomy in some detail.

There’s also data for Deity (i.e., God), but its historical connections overlap so much with other (mostly Greek) deities that it’s not so useful for my purpose here.

Finally, I want to mention that the source data for the Mapping Metaphor project, The Historical Thesaurus of English, is itself a fascinating resource. It arranges the whole of the English language throughout history into an ontology with the three root categories represented by color in the above images: the external world, the mental world, and the social world. Any hierarchical ontology raises the usual epistemological questions, but I think the approach is fascinating. The result is effectively a cultural ontology (at least to the extent that language encodes culture).

I compared a few Historical Thesaurus entries to the Lexham Cultural Ontology (designed for ancient literature) and found a surprising degree of correlation: all the entries I looked up in Lexham mapped to one or a combination of two entries in the Historical Thesaurus. Considering that we know (pdf, slide 33) that people who write linguistic notes in their Bibles are more interested in the meanings of English words than they are in the definitions of the original Hebrew and Greek words, I wonder whether an English-language-based ontology might prove a fruitful approach to indexing ancient literature–at least for English speakers.

Via PhD Mama.