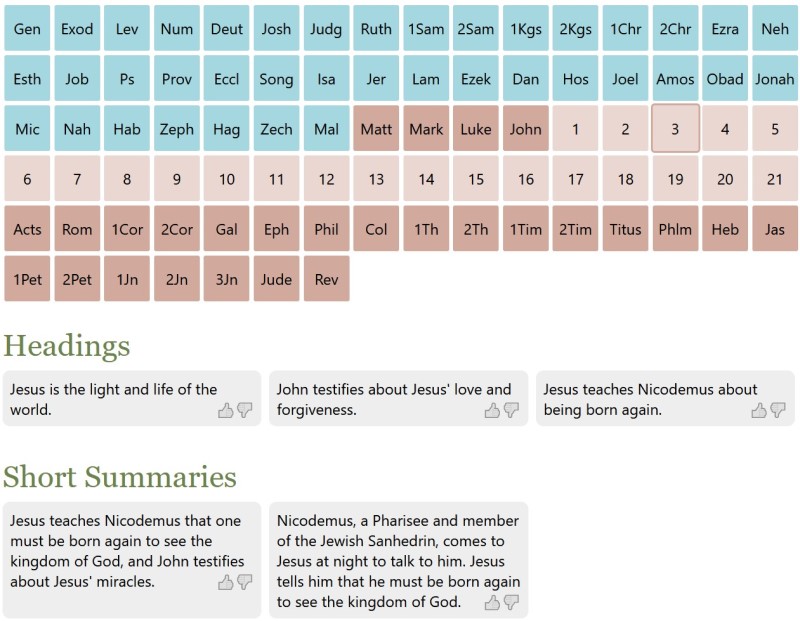

Bible Gateway recently shared their most-popular Bible verses of 2014, and I wanted to discuss this chart a little more:

The chart stems from the idea that if someone is equally likely to see a verse on any day of the year, each day should have 1/365, or 0.27%, of a verse’s yearly popularity. This chart shows days when there’s a spike in pageviews for each verse for a particular day (whenever it was over 0.4% of the annual total).

The theme of the chart is that people follow certain paths through the Bible during the year; I labeled a few of them on the chart. But there are definitely a few patterns I can’t explain:

- At the beginning of the year, two lines emanate from Genesis that look like they’re on track to read the full Bible in a year, but one of them is faster than the other. Why are there two?

- At the bottom right of the chart is a shallow line that looks like it involves reading Genesis and Exodus starting in May and ending in December. There’s a similar line in the New Testament running through Matthew from June to November. What are those?

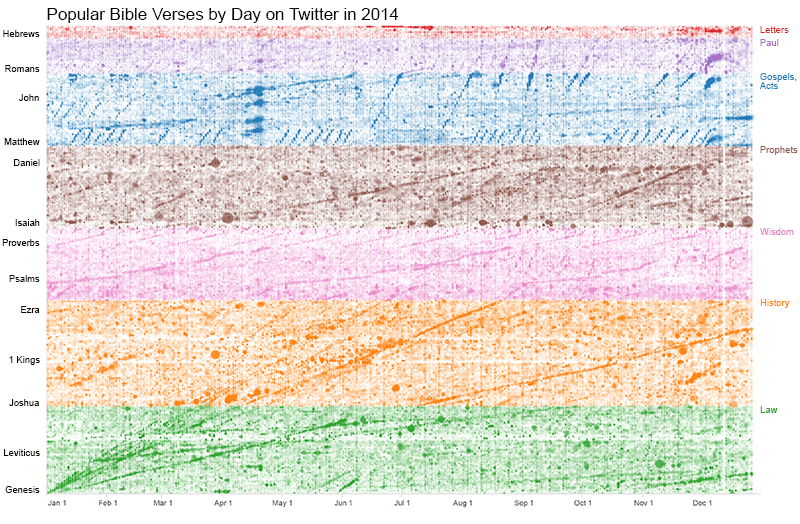

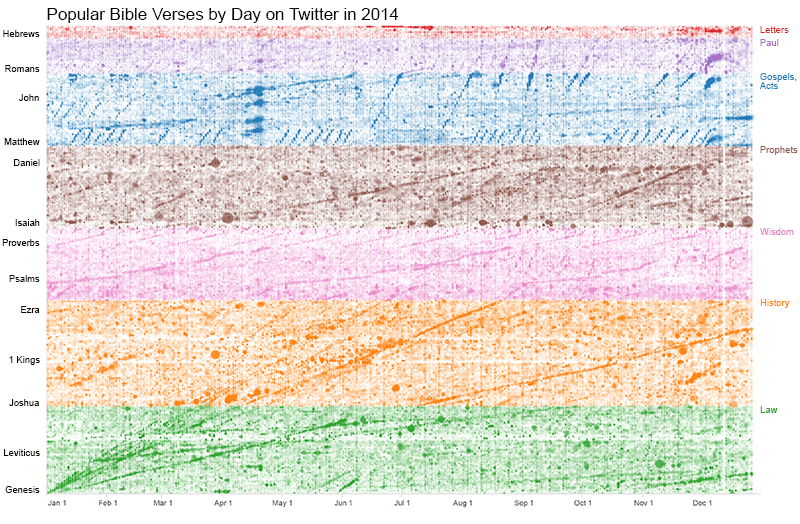

I was curious whether the same patterns would appear in Twitter for the year, so I ran a similar analysis on the 43 million tweets this year that mentioned Bible verses. The answer is that, yes, you can see many of the same paths in both charts:

They even include the same two (or three or four) fast readings of the Bible at the beginning of the year and the slow reading of Genesis and Exodus in the second half of the year. You can see similar peaks around the Passion stories leading to Easter and the Nativity story leading to Christmas. (Christmas is the last day that appears on this chart.) The Twitter chart more clearly shows the weekly rhythms of the devotional life, with vertical lines just barely visible every Sunday. The main difference is that there’s not as clear a path through the New Testament.

The Twitter chart also shows some horizontal bands where sharing is pretty light. These “sharing shadows” appear in the opening chapters of Numbers, 1 Kings, and 1 Chronicles.

Prolific Verse Sharers

A quirk of the Twitter chart is that some Twitterers tweet (and are retweeted) a lot. I suspect many of them are bots, but it’s hard to say whether they constitute “Bible spam”–many people do appear to find them helpful by retweeting them. The top fifty or so Twitterers are responsible for 16 million of the 43 million tweets this year. The chart doesn’t look too different if you remove them (mostly, the frequent repetition of Matthew disappears), but that just could be because I didn’t remove enough users to affect the results meaningfully. For all I know, this chart mostly just shows how Twitter bots share the Bible during the year. The consistency with the Bible Gateway data (in which I have more confidence), however, leads me to think that this picture is reasonably accurate.

Here are the top non-bot (as far as I can tell) sharers of Bible verses–these people tweeted the most Bible verses (and, more importantly, were retweeted most) throughout the year. Some of these people I recognize, and others… not so much. The “tweet” numbers reflect only tweets containing Bible verses and include others’ retweets of their tweets.

- JohnPiper (105,836 tweets)

- DangeRussWilson (87,382 tweets)

- WeLiftYourName (52,638 tweets)

- JosephPrince (50,889 tweets)

- BishopJakes (49,109 tweets)

- siwon407 (48,994 tweets)

- RickWarren (42,637 tweets)

- JoyceMeyer (39,703 tweets)

- jeremycamp (32,003 tweets)

- DaveRamsey (28,173 tweets)

- RCCGworldwide (26,731 tweets)

- AdamCappa (25,976 tweets)

- Creflo_Dollar (24,422 tweets)

- sadierob (20,068 tweets)

- Carson_Case (19,846 tweets)

- TimTebow (18,303 tweets)

- Kevinwoo91 (17,230 tweets)

- levimitchell (16,355 tweets)

- jesse_duplantis (15,755 tweets)

- kutless (14,806 tweets)

Most-Popular Verses

Here are the most-popular verses shared on Twitter in 2014:

- Phil 4:13 (613,161 tweets)

- 1Pet 5:7 (261,417 tweets)

- Prov 3:5 (218,019 tweets)

- John 14:6 (212,883 tweets)

- John 13:7 (207,084 tweets)

- 1Cor 13:4 (197,379 tweets)

- Matt 28:20 (187,407 tweets)

- Ps 118:24 (183,475 tweets)

- 2Tim 1:7 (182,758 tweets)

- Ps 56:3 (180,139 tweets)

You can also download a text file (411 KB) with the complete list of 2014’s popular verses.

John 13:7 (“Jesus replied, ‘You do not realize now what I am doing, but later you will understand.'”) is the oddball here, but it turns out that it’s mostly from over 100,000 retweets of a single tweet in April. (Since it was a one-off, I omitted him from the list of top sharers above, although his tweet count of 163,497 would put him in first place.)

How do the year’s most-popular verses compare among Bible Gateway, YouVersion, and Twitter? The answer: there’s a good deal of variation. Below are the top ten from each service; only Proverbs 3:5 appears in all three lists, and YouVersion and Twitter only have one verse that overlaps, which surprises me (given that they’re both based on sharing).

If we look only at Bible Gateway and Twitter, the average verse differs in its ranking by about 3,000 places, or nearly 10% of the Bible. The largest differences in rank: 1 Kings 20:14 is much more popular on Twitter (rank 4,380) than on Bible Gateway (rank 27,119), while Ezra 5:14 is way more popular on Bible Gateway (rank 13,995) than Twitter (rank 30,018).

Bold entries appear in at least two lists.

Data Source

The Twitter data is from Bible Verses on Twitter. A program connects to the Twitter Streaming API with a query for every chapter of the Bible (“Gen 1”, “Genesis 1”, and so on). I run a Bible reference parser on the tweet to pull out all the references. Then an SVM algorithm tries to guess whether the tweet is actually talking about a Bible verse or just happens to contain a string that looks like a Bible reference (“Gen 1 XBox for sale,” where “Gen” is short for “Generation”).

Sidenote: How I Calculate Verse Views

A note on methodology: I’ve never documented how I determine a particular verse’s popularity; now’s a good time, because you can do it a number of ways to reach different answers. Let’s say that someone is looking at Genesis 1, which has 31 verses. That counts as one pageview, but if you’re looking for the number of pageviews that, say, Genesis 1:1 receives, how do attribute a chapter-length view like this? You could give each verse credit for a full pageview, but then verses in long chapters will appear to have a disproportionately high number of pageviews. Instead, I prefer to divide the pageview into the number of verses in the passage: in this case, each verse in Genesis 1 will receive 1/31, or 0.032 pageviews.

Now, what if someone is looking at, say, Genesis 1:1 and Matthew 1 (25 verses) on the same page? In this case, I divide the pageview by the number of separate passages: Genesis 1:1 receives credit for a full 0.5 pageviews, as does Matthew 1. Each verse in Matthew 1 therefore receives 0.5/25, or 0.02 pageviews.

I feel that this approach best respects people’s intentions whether they want to look at multiple verses, several independent passages, or just individual verses.